The trouble with Rosetta Stone

Merry Christmas my dear readers! Few though you may be….

After marrying my wife in the Philippines last year, I’ve been trying to learn Tagalog (Filipino). For most languages there are perfectly adequate (if not well-designed) free courses available, but I couldn’t find a free course for Tagalog. Even though this language has almost 100 million speakers, courses in Tagalog are almost as scarce as software that is localized for it! Apparently, being a poor country means people don’t want to learn your language.

So I’ve been using Rosetta Stone — an old version, mind you. Version 3.

Rosetta Stone is the course that teaches through “immersion” — no English at all, just Tagalog the whole time. The concept isn’t bad, and although there are certain things that are hard to teach in an immersion situation, such as grammar and abstract concepts, I do think that all the most important things could be taught this way if the course were well designed and you were to spend enough time on it.

However, I do not think Rosetta Stone is well designed. In fact, I think that the whole “immersion” thing that they use as a selling point is actually just a business strategy. Think about it: immersion allows Rosetta Stone to sell their course to the whole world, whereas a course like “Tagalog for English speakers” can only be sold to English speakers. Immersion, combined with their high prices, is intended to create a cash cow.

First, let’s talk about the overall design.

It has a voice recognition system, but I’m ignoring it. It is supposed to tell you if you are pronouncing words correctly, but for some reason it doesn’t work on my laptop (maybe because its built-in microphone is kind of lousy). I could buy a new microphone but I’m fine without it — I just have to remember to practise speaking. I would do that anyway.

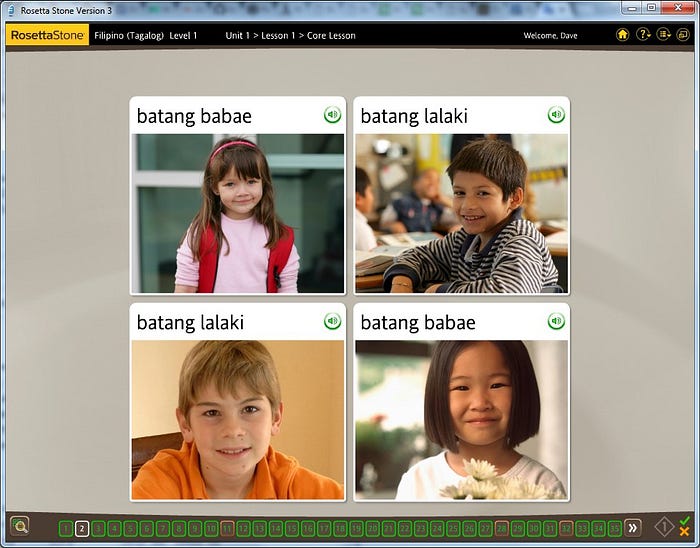

Aside from that it consists of about 93% multiple-choice questions. The majority of the time you are shown four pictures and asked to match them with four sentences or phrases, which are usually spoken out loud so you get used to hearing them. Sometimes you have to choose one of four pictures for a sentence; other times you have to pick one of three sentences for a picture.

There are some good things about it. For example, some courses emphasize individual words while Rosetta Stone emphasizes full sentences. This is a good, since knowing all the words in isolation does not help you to understand or to write fully-formed sentences.

But on the whole, I’m not impressed with the product.

The Two Biggest Issues

Rosetta Stone’s biggest problem is that it does a poor job stressing or testing your memory. Once you get the hang of it, matching four sentences to four pictures is pretty easy, and to make things easier, it keeps asking the same questions over and over. Each “lesson” (1 to 2 hours long) is broken into parts, starting with a long “core lesson”. Each of the other parts is a little different (e.g. in one part you only hear the audio, while in another part you only see the text), but every part re-uses the same multiple-choice questions, with the same sentences, from the core lesson. This means that you will naturally rely on your memory of the question (and which words, sentences and pictures appear together) to help you answer each question. I realized I was getting scores of nearly 100% without really learning the words — I was learning just enough about how the four sentences are different from each other to be able to answer the questions.

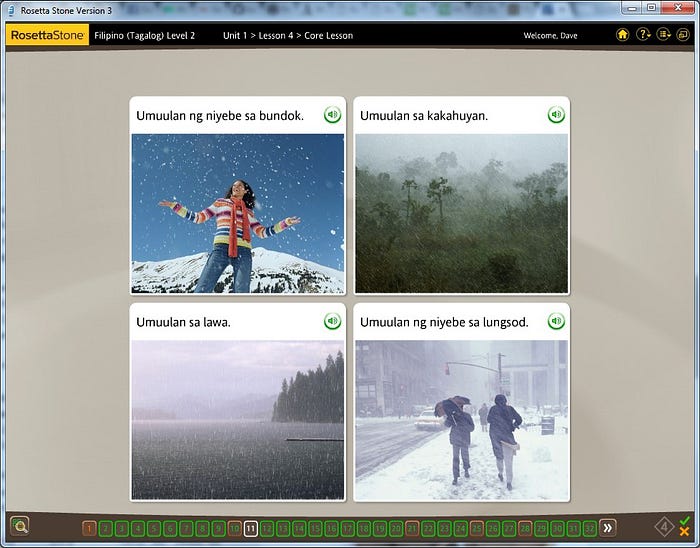

As an example, Let’s talk about these four words which I really did not learn even though I can answer Rosetta Stone’s questions about these words with 100% accuracy:

- lawa: lake

- bundok: mountain

- kakahuyan: forest, or maybe woodlands

- dalampasigan: beach, or maybe coast or shoreline

Since these four words usually appear together, can you guess why it was easy to tell them apart without really learning them?

They are different lengths. Learners naturally take the path of least resistence, and it’s easier to remember a word’s length than the actual sounds it is made of. So I picked up on the fact that the really long word is “beach” and the shortest one (which I remember starts with “L” as in “lake”) is “lake”, and the other two-syllable word is “mountain”. That’s all I need to know to answer the questions.

You see, Rosetta Stone does not mix words from different pages often enough. If there were more variety, this would be less of a problem. As it is, I have tried to stress my memory more by closing my eyes before each question starts so that the pictures do not help me understand the audio (not all questions begin with a spoken sentence, so if I don’t hear anything I open my eyes again.)

Again, since the questions are multiple choice, you almost never have to actually remember any words; at most you just have to recognize them. If that wasn’t easy enough, other elements of the sentences usually tell you what an unknown word means. For example, if a sentence says “the man eats rice”, and you completely forgot the word for “rice” but only one of the pictures has a man eating alone, then you know the answer. In fact, I regularly click the answer before the sentence finishes speaking because the sentence contains an obvious clue (and I’m getting bored).

Rosetta Stone never breaks out of that habit of letting you “cheat” and figure out the answer contextually. If you’re really not learning the new words very well, then as long as you have learned Rosetta Stone’s favorite words like “man”, “woman”, “boy” and “girl” and a few other very common words, you can “fake” your way through many lessons and get almost 100%. But your sense of achievement will be short-lived, because when you come back to Rosetta Stone the next day to take the next lesson, you’ll find yourself suddenly stumped and confused when they finally give you a sentence that actually requires you to understand a word from the previous lesson — a word that never made it past your short-term memory. At that point it’s too late, as Rosetta Stone provides no way to study a word again without repeating the entire previous lesson.

This is a big flaw. Rosetta Stone often gives you the feeling that you’re learning when in fact the words are only vaguely imprinted on your short-term memory, a low-quality memory that is good enough only to recognize words, but not recall them.

The only non-multiple choice part is “Writing”. This is just a small part of each lesson, and it consists mostly of listening to sentences and then writing them down. Since Filipino is phonetic, this is fairly easy, but still the hardest part of each lesson. The rest of the course needs more difficulty, too.

The other key problem with Rosetta Stone is that it fails to use new words at the correct frequency. When a lesson introduces new words, it uses those words very frequently, which is good. But in the very next lesson, some of those words will not appear at all.

The right way to teach involves “Graduated Interval Recall” (a key component of the Pimsleur method of language learning). This means that a word is repeated very often at first, but gradually it appears less frequently. Frequency must decrease gradually: each time you encounter a word, it strengthens your memory of that word, so if a course suddenly stops using a word before you fully learned it, you will forget it. That’s the second biggest sin of Rosetta Stone. Most words are rarely used after the lesson that first teaches them. The software mitigates this problem somewhat by interleaving lessons together (i.e. parts of lesson 2 are inserted in the middle of lesson 3) but this is not a complete solution, and I have forgotten up to half of the words I learned because they just stopped appearing.

Ideally the software would recognize which words I seem to know the best and use those less often, instead emphasizing words I struggle with. Unfortunately, Rosetta Stone uses fixed, pre-planned lessons which waste my time on words I already know like “doktor” and “ospital” while failing to repeat words that are difficult.

Here are some other problems with Rosetta Stone.

It neglects important words and phrases

Generally, Rosetta Stone has the good sense to teach common words first (like apple, man, woman, door) rather than less common words (such as crate, eyebrow, or prothesis).

However, some very common and important words, phrases and sentence structures are not taught early enough. I’ve learned two other languages and made quick references for Spanish and Esperanto, so I have a general sense of which words are the most useful for basic communication.

I’ve taken a little over 20 lessons now — that’s at least 30 hours into the course. Note that each “level” consists of 16 “lessons”, so I am in Level 2. After 20 lessons they still have not introduced important verbs such as:

- is (Filipinos may not use the word for “is” often, but it does exist and is extremely useful for beginners.)

- become/get (as in “I get sad”)

- find/found

- happen

- help

- know

- let/allow

- mean (as in “what does that mean?”)

- put

- say

- should

- start

- see

- seem

- take

- think/believe

- understand

- use

I could make a similar list of other words I wasn’t taught, like “easy”, “difficult”, “empty”, “full”, “important”, “long”, “strong”, “thing”, “road”, “ground”, “food”, or “again”. They didn’t teach the word for “good” and “bad”, even though they did teach the words for “smells good”, “smells bad” and “rotten”. Strange! And they taught the words for “smell”, “listen” and “watch” but not for “see”, “touch”, or “feel”.

Also, key phrases have not been taught that you would need for basic communication, like

- “I don’t speak Tagalog.”

- “I don’t know.”

- “I don’t understand.”

- “Oh, I understand now.”

- “Can I help you?”

- “Could you say that again?”

- “What is the word for this thing?”

- “What should I do?”

- “What do you want?”

- “Where is the bathroom?”

- “What happened?” / “What is happening?”

It ignores language shortcuts

Rosetta Stone emphasizes full sentences, which is good, but neglects to teach shorter forms.

For example, it teaches “malawang galang na po” which seems to mean “excuse me”, but Google Translate doesn’t recognize that phrase. My experience in the Philippines is that people actually just say “excuse po”. It also teaches “salamin sa mata” for “glasses”, without teaching you that “mata” means “eye”. Google, however, suggests simply “salamin” as the translation of “glasses”, and “salamin sa mata” is not on its list of alternate translations.

Also, they use the phrases “kapatid na babae” (sibling female) and “kapatid na lalaki” (sibling male) over a hundred times without introducing “ate” (sister) or “kuya” (brother), which my Filipino family seems to prefer. Maybe that’s okay; Google Translate thinks that the “kapatid” phrases are more common.

100% Linear

Rosetta Stone expects you to start at lesson 1 and proceed linearly through each course, beginning to end. It has no features for reviewing what you have learned. There are not even any word lists associated with the lessons.

And the lessons do not have names! They are identified simply by number, there are no summaries of what is in each lesson. So there is no way to find out what is in a lesson except by entering the lesson again (as you wait for Rosetta Stone’s sluggish user interface to slowly respond to your clicks).

Poorly designed pictures

Remember, since translations are never provided, the pictures are the only thing that expresses meaning, so it’s very important for them to be smart about which pictures they use (and which sentences they use).

But Rosetta Stone gets lazy sometimes. The majority of pictures are clear, but there are more than a few frustrating cases where a picture is ambiguous and might seemingly match multiple sentences in the question.

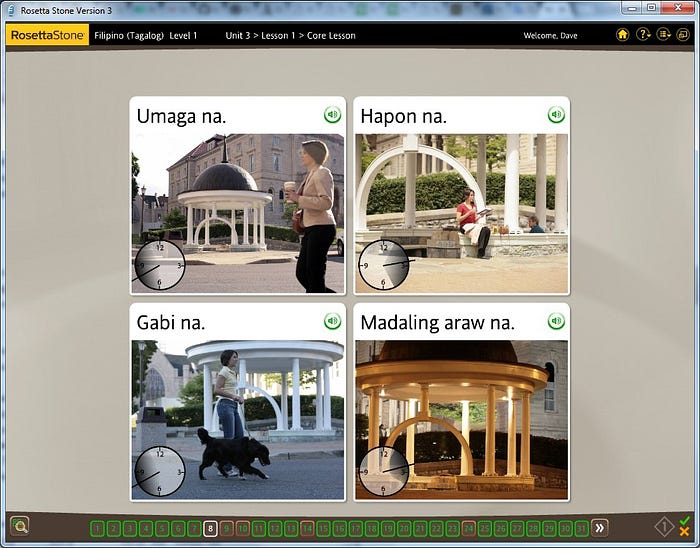

For instance, when it teaches the words for “morning”, “afternoon”, and “evening”, it overlay analog clock icons to indicate the time of day. So 8 AM and 8 PM look identical on the clock, and the amount of daylight in the picture doesn’t help (in some seasons and places, 8AM is dark; in others, 8AM is light, and likewise for 8PM). Instead we’re expected to figure out that “woman holding a coffee cup” means it is morning, while “woman walking a dog” means it is evening.

There are also a small number of outright errors which might confuse learners. For example, Tagalog has two different words for “we”: “we including you” and “we excluding you”. So a picture of a family talking to you (the camera) might be attached to a picture that says “Pamilia kami” (we are a family, not including you), but a picture of a family talking to each other would say “Pamilia tayo” (we are a family, all of us). However, in one picture people are looking at the camera and using the word “tayo”, which is wrong and confusing.

Lack of subtlety and detail

Using only still pictures, it’s hard to explain subtle things, and Rosetta Stone usually does not try. For example, my wife tells me that (surprisingly) the word “gustó” means both “want” and “like”. But taking the course, you would likely be confused about whether “gusto” means “want” or “like” (or both) because the still picture that describes someone “wanting” something or “liking” something would usually look pretty much the same (a woman looking at jewelry in a glass case, for example, or a boy reaching his hand out toward chocolate.)

You can imagine pictures that would clarify: a man might “like” chocolate but not “want” it when he is full. I might “like” an iPhone but “want” an Android. And he might “want” bad-tasting medicine but not like it. If “gusto” has both meanings, you could maybe say something like “Gusto kong tsokolate, pero hindi gusto kong tsokolate ngayon.” (“I gusto chocolate, but I do not gusto chocolate now” — though this, too, would be confusing, since ngayon means both “now” and “today”. I wonder what Filipinos would actually say.)

Similarly, the course does a terrible job explaining the difference between “aalis” and “darating” (depart and arrive, respectively). None of the still pictures clearly distinguish a vehicle leaving from a vehicle arriving, and while you can maybe infer the difference from some of the questions, it’s not easy.

Rarely do they provide enough information for you to tell what a word does not mean. Where are the boundaries? For instance, they were smart enough to realize that students would not see the difference between “kailangan” (need) and “gusto” (want), so they made pictures like a sick child refusing medicine, with the sentence “The boy needs the medicine but does not want it”. And a picture of a woman looking at jewelry: “The woman wants the jewelry but does not need it.”

However, “aalis” and “darating” were only used to describe what planes, trains, and buses do. Does this mean that a person, or a taxi, cannot “aalis”? Or is it simply something they forgot to show?

How about “dalampasigan”? This word was always shown together with a beach. The course could have also shown a rocky shoreline, or cliffs beside water, and told us whether or not that counts as a “dalampasigan”. They could have shown sand without any water and told us whether that is also a “dalampasigan”. But they didn’t.

Botched presentation of verb tenses

Teaching Tagalog verb tenses demands a very careful presentation, because from what I’ve heard Tagalog has a fairly large set of verb conjugations — it’s not as bad as Spanish, but it’s more complicated than simply past, present and future.

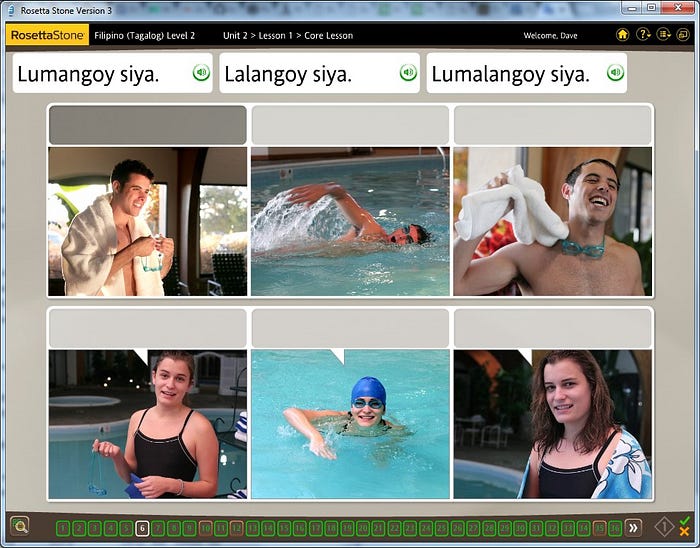

But when Rosetta Stone finally, in lesson 20, introduces past, present, and future tenses (after having occasionally used non-present tenses at random earlier in the course), it does a poor job of representing time: which pictures indicate that something happened in the past and which ones indicate that something happened in the future?

At first they had a good idea:

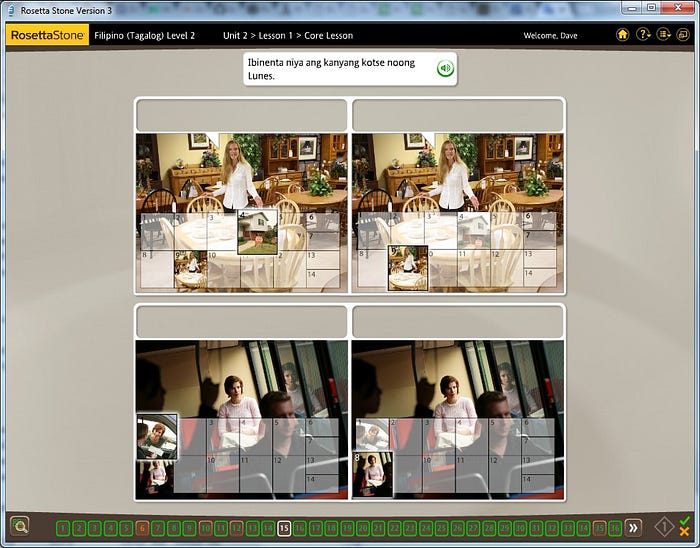

Really the man and woman should be wet after leaving the pool, but the idea is good: tell a story with the sequence of pictures, so that the future tense is on the left and the past tense is on the right. But this intelligent presentation was quickly abandoned in favor of this confusing mess:

Here they have introduced a new word, “Ibinenta”, which apparently means “sold” even though it doesn’t look like the word previously introduced for sell, “nagbebenta”. Rosetta Stone expects the student to look at the tiny thumbnail of a man in a car and infer that the woman has sold her car to the man (and now rides the bus), even though “ibinenta” is a new word that the student has never seen before. Simlilarly, when you see the tiny thumbnail of a house with a sign in front of it, you’re supposed to figure out that the woman just bought a house.

So, it’s a challenge at first. That’s not the biggest problem though. The biggest problem is that Rosetta Stone doesn’t help the student see any pattern between the past, present, and future tenses of the different verbs.

Here are a few of the verb tenses, as best I could piece them together from Lesson 20: past tense first, then present, then future. Some words seem to have two present or two past tenses, but the lesson seems oblivious to this uncontrolled proliferation of verb forms:

- Buy: Bumili / Bumibili / Bibili

- Swim: Lumangoy / Lumalangoy / Lalangoy

- Eat: Kumain OR Kinain / Kumakain / Kakain

- Read: Magbasa / Nagbabasa OR Binabasa / Babasahin

- Sell: Ibinenta OR Nagbenta / Nagbebenta / ??? (future tense not given!)

- Visit: ??? (past tense not given!) / Binibisita / Bibisitahin

- Play: Naglaro / Naglalaro / Maglalaro

You might be able to see a pattern between some of these. For example, the words for “buy” and “swim” seem to follow a pattern, where the future tense duplicates a syllable (bibi, lala), the past tense adds “um” (bumi, luma), and the present tense does both of those (bumibi, lumala).

However, the course is presented in a disorganized way so that the patterns are hard to make out, and clearly, not all the verbs follow this pattern.

For the most part, Rosetta Stone does not present the three tenses together (it often shows different tenses on different pages) and it does not compare different verbs to each other to show when different verbs follow the same pattern. And since it takes about three seconds to switch between two pages, you cannot easily compare verbs that were presented on different pages.

To make matters worse, some tenses of some verbs weren’t shown at all, while some verbs seem to have two present tenses or two past tenses. What the hell is going on here?

Then, to add confusion, they throw in the new words “binigyan” and “ibinigay” at the end of the lesson, without clearly indicating their meaning, and they immediately start using multiple tenses of those words. Great.

Lack of grammar & lack of variety

The “grammar” parts of Rosetta Stone are a joke. They just color certain words or parts of words red, or blue. What’s that supposed to mean? Who knows. Sometimes it draws my attention to some pattern or relationship, but often the thing it seems to be teaching is something I had already realized earlier.

The subtlety of verb tenses especially seems to call for at least a small amount of native-language explanation. Also, Tagalog seems to use adjectives as verbs, and verbs as nouns, in very strange ways which are neither explained nor explored very thoroughly by Rosetta Stone.

Rosetta Stone occasionally throw a sentence or two at you with a completely bizarre structure and grammatical markings you’ve never seen before, but it doesn’t explore variations of that structure that might help you make sense of what’s going on. After using a strange sentence structure a couple of times, they quickly return to the old familiar patterns and let you forget about that strange beast you just saw.

Often a language offers many ways to say essentially the same thing, with the same basic meaning but different nuances. For instance, you probably understand the role in English of emphasized words — “My car is broken” has a slightly different meaning from “My car is broken”. My Filipino wife did not understand, apparently, how this works and I had to explain it to her, despite her many years of experience with English. So I suspect Filipinos achieve emphasis in some other way, probably by actually changing their sentence structure, though I have no idea how this works yet, and I have no faith that Rosetta Stone can explain such subtleties.

Typically, Rosetta Stone consistently uses the same patterns of sentence structure over and over; most sets of four sentences use the same structure in all four sentences. This is a good thing at first, when starting a course or a lesson in the course, because too much variety would be bewildering and confusing. However, once you’re comfortable with a certain sentence structure, it becomes a waste of time for the app to keep repeating it ad-nauseum. In real life you rarely see the same sentence structures four times in a row; people deliberately change it up. But Rosetta Stone keeps using the same structures four times in a row, often using the same structures it has been using since Unit One.

How many common sentence structures, I wonder, are they hiding from me?

Boring parts

Rosetta Stone doesn’t let you customize the pace to your needs. For me, some parts of the course are easy and I’d like to go through them quickly. That’s not allowed.

Delays in the user interface got irritating quickly.

First, there is a sound that plays every time you get a question right, and you have to wait for the sound to finish playing before it moves to the next question. Luckily, you can turn off the sound, but in that case you still have to wait for an animation where the selected sentence moves over to the picture (luckily this animation is shorter than the sound).

Second, in many (30%?) of the questions, the selected sentence is spoken after you select it rather than before. So first you have to wait for the animation, and then you have to wait as the sentence you already chose correctly is spoken out loud.

Third, there is an animation after the first two of four questions where the pictures on top shift upward to make room for new answers to appear.

Fourth, after completing a set of (typically) four pictures, you have to wait for a few seconds until it starts moving to the next screen. I turned this off so I can manually control when it moves to the next screen, but after clicking the tiny “Next” button, it still spends two or three seconds fading to the next screen.

Other boring parts of Rosetta Stone:

- having to study words you know already, like words in Tagalog that were taken directly from English.

- the lack of interesting things happening in the pictures.

- the ridiculously easy “Reading” parts in the early lessons. In these sections you are given single syllables like “ko” and “ka”. A voice will say “ko” and then you have to choose whether he just said “ko” or “ka”. How dumb do they think we are? To me, what’s really boring is not so much that the questions are easy, but the fact that you have to wait for the animations and voice enunciation between each question. Can we get on with it please?

Conclusion

Rosetta Stone isn’t bad, but it has numerous shortcomings in its approach to teaching. Once you get the hang of it, you may find it is paced too slowly even though you are not learning the words very well. While Rosetta Stone’s immersion concept is a powerful idea, for adult learners it’s not very practical to teach everything that way. Finally, while you may learn to understand a language with Rosetta Stone, you’re not really learning to speak it since you never have to invent new sentences during the course.

Other issues:

- Culturally irrelevant content: almost none of the pictures have Filipinos in them; local Filipino food is not shown (except rice); and money is in dollars and euros rather than pesos. Obviously they’re saving money by re-using the same pictures for all languages taught by Rosetta Stone.

- It’s a memory hog. I can’t imagine how such a simple app needs 500MB of RAM.